The following is an edited text of an interview that took place between Ornela Vorpsi and artist & writer Vladimir Myrtezai in February 2018.

Vladimir Myrtezai: COD is the hosting space for your exhibition and can be deciphered as an opportunity for cultural dialogue. Yet, in Albanian, the first word that immediately comes to mind upon hearing this word, Code, is one usually associated with a secret message, figures or other words with which modernity shackles us to in the name of security. What does the existence of an open centre in the heart of this emblematic building of power mean for you?

Ornela Vorpsi: The very existence of this beautiful centre is so meaningful. You don’t expect a government to make such a thing. And in fact, I have not heard of something like this done before, either in Albania, or elsewhere. For me, the real politics are, first of all, education and culture. And when a government endeavours to enhance education and culture, it takes a big, humanist step forward. Especially in a country like ours, where in a blink, the people have gone from a status of collective extreme poverty to a headlong individual race at all levels for swift enrichment or benefit of any kind, about which they relentlessly live or fantasize about. I believe only in education and culture. So I admire every effort, no matter how big or small, that seeks for ways that build man up from the deep end. In short, I am happy to exhibit in such a space, unique in its kind for the artist and the citizen, where the interaction between the two happens without any censorship or obstacle in this ultimate palace of power.

VM: Given that the artist’s fascination with power has its own costs in terms of independence and judgment, does this bother you or complicate your position?

OV: Sorry, but in the context we are in and the case we talk about, I can say that these are simply tales that art craftsmen and sophists tell each other. These are words said by those who give and take to make sure the other is resisting seductions or addictions. These words, in fact, are fully imaginary. And forgive me but also quite ridiculous. Myself, I’m not in the slightest distressed or bothered by this. On the contrary, this opportunity to now “conquer” spiritually and aesthetically, with my parables and artworks, the entrance hall of a building that once embodied, for all of us, the power and the fear of yesteryear, honours and excites me. These days, the people, those below and those above, have the right to overcome this very threshold of power that, until yesterday, was unthinkable for us! No free artist or a free man, one unperturbed from the tales of those art craftsmen, who always take the default opposite seat between art and power, would hesitate to take advantage of the unique possibility to invade and exhibit in the very heart of this palace of power.

VM: As a concept of power, does it frighten you to be free today, outside the protection of man-made walls?

OV: The only thing that frightens me today is myself. I do not feel free or restrained just because the concepts given by the society or art, dictate this way or that way, right or left, up or down. I have my parameters, undistracted by current trends or fashions. What fascinates me is the Truth. A real exchange with the other, a real stand in the world. This is my parameter, and it fills me.

VM: There is an echo that still reverberates around even today: Ornela Vorpsi as one of the city’s most beautiful girls. Does it worry you that many people might remember you for your beauty rather than your work? What is the balance between something that does not depend on a human being (beauty), and something that does depend on her (her oeuvre)?

OV: No, it does not bother me at all. Since I have not yet achieved the required wisdom (and I am convinced I never will), the vanity within me enjoys this fact, even though, to tell you the truth, I never thought of myself as a benchmark of physical beauty, not at all. So I’m always surprised when people say this to me. Nevertheless, the echo of the past does not take away the value of my work for those who decide to make a step forward and meet it.

VM: So, what is the balance between something that does not depend on a human being (beauty), and something that does depend on her (her work)?

OV: I really don’t know what’s entirely up to us. Even these other things look to me like the faculty of beauty, they do not depend on us: talent, will. We tend to say that they depend on us but I think nothing depends on us. If they were dependent on man, all else (innate beauty aside) would be more convenient. For example, I would choose to have the will of steel, tremendous talent, wisdom … and so on.

VM: For a creative person, childhood is a spell of magic from where we take and give illuminating signs. Then comes adolescence, adulthood, first love and so on. For example, in adolescence, I felt older than the others and fell in love with my physics teacher. On this spinning ground is there an unnatural “accident” that happened to Ornela Vorpsi? A forbidden love? An impossible love? A borderline desire from youth to be overcome, transcended?

OV: I was excessively romantic. I believe a part of me still is. I fed off literature and saw the world through this literary prism. My first (platonic) love was at the age of 16. I saw him on a bus coming back from practice. Our eyes met and the world stopped. From that day on, this boy followed me from school to home. We never talked, even though he made some attempts. I could not talk to him. He seemed terribly beautiful to me and I did not feel I was at the height of the miracle that he was. For a full year, he “chased” me. This is the word used back then. Then he disappeared. I was told he had fallen in love with someone else. This “accident” is usual, natural. To date, whatever “accidents” have happened to me may befall any human being.

VM: Since you are someone affected by the regime we left behind, can you tell us something about your relationship with the past? A significant amount of time has passed since then. It’s not easy now to nourish some kind of natural revolt against all that pressure, a pressure that only those who suffered through it can know: hate, contempt or a state of anxiety translated into a love-hate mood swing? Does the phrase “dear enemy” say something to you?

OV: I have none of these, dear Vlad. I just feel that I need a sort of distance from an Albanian mentality that I still find it hard to digest. I hate megalomania, hypocrisy. Clearly, I have not forgotten the psychological violence that I have lived through, that is impossible to forget. But even this violence has contributed to make me stronger, to make me who I am today.

VM: Artists are unique beings and we assume that they are not always at the right place and at the right time. Do you trust this “natural law” that either justifies them, or reveals them as beneficiaries of a lucky break?

OV: The truth is they are not always in the right place. What is the right place? It must be the place where man finds the opportunity to find a break in the most meaningful way for himself and in society – this is the idealistic viewpoint. Imagine if Michael Jackson or Picasso were born in the Albania that our generation has known. They would not be those figures we know today. Life is and remains a mystery. I’m not saying anything great here. Many things are what we banally call luck.

VM: What is life for you: an excuse for existence, a natural pretext, a tedious journey towards recognition, or…

OV: A philosophical question! It brought a smile to my face because I lived these three things. As a child, I was still a natural pretext, tormented (in my case) by many existential questions. As regards the tedious journey to knowledge and justifying human existence, I underline that existence does not really need justification; it is an end in itself. But I have often felt and I still feel that I need to “justify” my existence (be this through my artistic work or the ethical approach with which I proceed through the daily rituals in my life). These two processes work in parallel within me, even today. Life for me is also this feeling: Oh, one day all this noise will end! And death will be like going to sleep in a bed with clean sheets after a daunting day, i.e., willingly. Living is a very tedious exercise. What a miracle that I am mortal!

VM: Artwork, is it just a cause or a human need? Is it a sophisticated personal thrill or an organ in the anatomy of communication?

OV: And who am I to give a correct answer to this question? So I’m responding with all my limits that cast me as Ornela. An artwork is a human need, a ground for meeting and consolation, sometimes even vanity.

VM: Loneliness: an overdose that produces writers. Do you share the same opinion?

OV: Even before, I was kind of lonely. On the other hand, I have known many writers who are not lonely at all.

VM: If you could choose, would you like to live in a lonely alley, in an oxygenated forest with memories, or in a daily collision where the intensity of independence is narrowed down?

OV: In a lonely alley.

VM: One can see you as an artist shifting between many media and genres. Do you do this to shift the walls that routine concept and behavior build?

OV: Yes, to stretch my limits, to discover and prove myself, especially to educate myself.

VM: In a historical or non-historical place of your choice, what would it take to define you as a creative person? An interchange of ideas or a wild behavior that builds an independent reality?

OV: The anarchy, the myth of Dionysus, an independent reality and a love for the Stoics – for I cannot be like them, and I find it quite hard to master myself.

VM: Is there a model that has inspired you in your life?

OV: There have been many people and artists that I have loved and still love. But unfortunately I do not seem to have a model. If I did, it would have perhaps led me along me the way.

VM: Is there something that has caused a crisis in you, to doubt your self-worth, or led to a misunderstanding?

OV: Contemporary art, the vulgarity in many aspects of today’s life. Perhaps only the forms change and the essence of life remains always the same.

VM: What view do you share? That we are political animals, or that we are the most sophisticated mechanism in the living world, repeating the species in cycles? Are we like our parents?

OV: Perhaps we are more sophisticated than animals, because we prey on each other even when we are not hungry. But we have the same rights, and these rights derive from the common misery both species experience. The suffering both sides know and understand raises us to the same rank.

VM: Are we like our parents?

OV: To some extent, we have something from our parents inside us. I feel the blood and the nerves of my mother, or my father, but fortunately we are also something else.

VM: Judging from your experiences as a traveller through some renowned cultural landscapes, do you think life would be a completely different proposition if the journey you have already accomplished starts anew? And what do you think about parallel lives, aliens and the afterlife?

OV: It is clear that if you take away my emigration (to Italy and then France), I would be a different story.

VM: And what do you think about parallel lives, aliens and the afterlife?

OV: About parallel lives, I don’t have any opinion. It is a fact that transcends me. About the afterlife, I think I would return to a state of pre-birth, unconscious, non-conscience. Trou noir.

VM. The more we know, the less we dare to be ourselves, to match the signs in a rediscovered act as a territory of creation. Do you think knowledge kills creation?

OV: There is a kind of hidden truth here. Unawareness or non-existence helps, but only to some extent. We need knowledge, knowledge up to the point where it does not hurt. It’s the story of a delicate balance. Like life itself.

VM: With Duchamp, art changed course. The traditional walls and aesthetic registers that kept it in place fell away. Now there is an open, continuous dialogue, with a tendency for a quick change of cultural elites. Where does Ornela locate herself on this map?

OV: On painting, with love and unaffected by fads and trends. On Truth, which, for me, is the only thing that reaches the deep ends and outlasts fads and chronologies.

VM: In the mind and conscience of the people, the body is a complex affair. Many female artists use it as a common medium to mark the physical frames of their own body, for example Marina Abramovic and Rebecca Horn. What pushes you to insist on areas somewhat dealt with by other artists? Do you feel there is always room for a message?

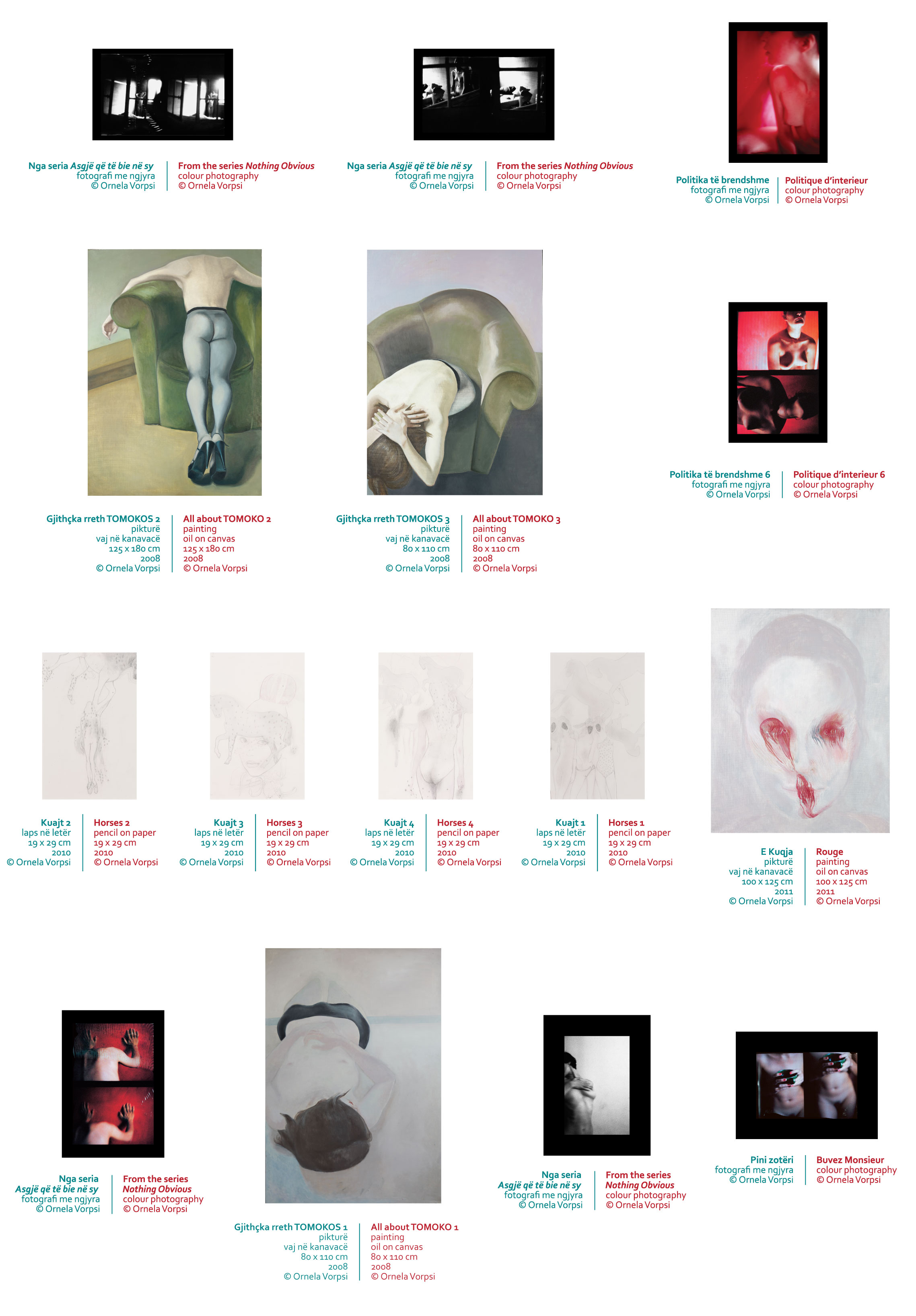

OV: There was a moment in my life when I made a journey around the woman’s body as “non-evidence” instead of the choice of preferring this or that body (the book Nothing Obvious). I had an inner need for this trip. I did not stop to intellectualize what I wanted. I was simply (and I am still) enthralled by the wonder of what we call existence.

VM: Is writing the experience of reality or a conception mot à mot of what is happening around you as artefact or testimony? And is it enough just to touch it, thinking that the magic of creation is to be found in a favourable circumstance?

OV: It is a difficult yet miraculous “track” that shapes you and, to reuse the word again, “educates” you. In my case, it has nothing to do with experiencing reality, but with a desire that comes from within me. It is a desire to conceive something that I call beautiful, beautiful according to my criteria, with the purpose of offering it and sharing it with others.